On November 20, 1900, newspapers in Washington, D. C., published stories about the killing of Black men in North Carolina and Colorado.

Greensboro, N. C. -- Judge Thomas J. Shaw, of the Superior Court at Rutherfordton, has issued bench warrants for six men, alleged to have been implicated in a recent lynching. The crime was committed some weeks ago, a Negro being lynched for killing a white man in an affray.

"Bench Warrants Issued for Lynchers." The Washington Post (Washington, D. C.). November 20, 1900. Page 3.

Chicago. -- The burning of the Negro Porter at the stake by the citizens of Limon, Colorado, will be brought to the attention of President McKinley by the Methodist ministers of Chicago. At a mass meeting held in the First Methodist Church, they passed a resolution censuring the governor of Colorado, the sheriff and the citizens of Limon who composed the mob, and resolved to request the President to call attention in his message to the 2,000 persons put to death by mobs in the last ten years, and urge him to recommend to Congress suitable legislation which shall secure to every person accused of a crime a fair trial and hold criminally liable any persons constituting mobs to torture, murder and burn.

"Censured by Ministers." The Evening Star (Washington, D. C.). November 20, 1900. Page 1.

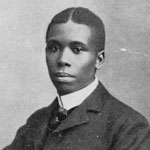

A few days later, Paul Laurence Dunbar's powerful poem about lynching, "The Haunted Oak," was published in Century magazine. It was accompanied by an illustration of a winged angel with its hands on its head in apparent anguish.

Pray why are you so bare, so bare,

Oh, bough of the old oak-tree;

And why, when I go through the shade you throw,

Runs a shudder over me?

My leaves were green as the best, I trow,

And sap ran free in my veins,

But I saw in the moonlight dim and weird

A guiltless victim's pains.I bent me down to hear his sigh;

I shook with his gurgling moan,

And I trembled sore when they rode away,

And left him here alone.I feel the rope against my bark,

And the weight of him in my grain,

I feel in the throe of his final woe

The touch of my own last pain.And never more shall leaves come forth

On a bough that bears the ban;

I am burned with dread, I am dried and dead,

From the curse of a guiltless man.Excerpt from "The Haunted Oak," by Paul Laurence Dunbar. The Century Magazine (New York, New York). December 1900. Pages 276 - 277.

Years later, a friend described how Paul got the idea to write "The Haunted Oak."

I remember being at Paul's home one afternoon, when an old ante-bellum friend of his who lived in the "Camp," a Negro settlement at the foot of Howard University, came in. He was very fond of those old-timers, and often used to invite them in when passing his home, give them a glass of beer, and listen to their stories about times down South "Before the War." This old man told a story of how down in Alabama, a nephew of his had been falsely accused of rape; how the "night riders" took him from jail and strung him up on a limb of a giant oak that stood by the side of the road. In a few weeks thereafter the leaves on this limb turned yellow and dropped off, and the bough itself gradually withered and died while the other branches of the tree grew and flourished. For years in that section this tree was known as the "haunted oak."

"Some Personal Reminiscences of Paul Laurence Dunbar," by Edward F. Arnold. The Journal of Negro History (Chicago, Illinois). October 1932. Page 401.

Soon after "The Haunted Oak" was published, Paul received a letter from his friend Brand Whitlock, an attorney who later became mayor of Toledo, Ohio. Whitlock praised the poem but questioned why Paul chose to portray the lynching victim as innocent. Two times in the text, the man is described as "guiltless."

I must tell you how fine and strong is your poem in this month's Century. When I read it aloud to Mrs. Whitlock last night her eyes filled -- and mine -- well, there's tribute enough for you. We have both so long felt what you expressed and I have thought deeply and painfully on all these problems. I would venture one question, in the nature of criticism. I would object to the suggestion of innocence, not because it isn't warranted, but for this reason -- Suppose he were guilty -- would it excuse the deed? The truth is, our whole system of punishment, of criminal law, of jails and gallows, is a barbarous anachronism and I grow sick of the brutishness which is always looking for a victim, guilty or innocent, legally or illegally. We must abolish punishment in all its heinous hideous forms and substitute love and forgiveness and compassion. All true poetry is prophecy, and you are a poet and a prophet, so your voice has a part in bringing these things to pass in a day long after our own time, perhaps, but in a day that will come.

Brand Whitlock to Paul Laurence Dunbar, December 5, 1900. Paul Laurence Dunbar Papers, Ohio History Connection (Microfilm edition, Roll 1).

Your criticism of "The Haunted Oak" is well taken, but had innocence been left out, I believe it would have destroyed one element of dramatic power essential to the ballad. Our feeling at a crime committed against a criminal is never as deep as that as an injustice done to an innocent man. This is not ethical but it is natural. But you are no more a part of our wrong system than I or any other man who lives complacently under this government, earns his bread and votes. Unless we live lives of protest, and few of us are willing to do that, we are as guilty as the lynchers in the south -- we are all tarred with the same stick.

Paul Laurence Dunbar to Brand Whitlock, December 26, 1900. Paul Laurence Dunbar Papers, Ohio History Connection (Microfilm edition, Roll 2).

Paul's letter points out that few people are willing to "live lives of protest" in the face of racial injustice. Booker T. Washington, for example, refused to comment on a lynching in Georgia because didn't want to risk losing financial support for the Tuskegee Institute.

"I would like to speak at length upon these Georgia occurrences and others of a like nature, which have taken place in recent years, but in view of my position and hopes in the interest of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and the education of our people, I feel constrained to keep silent and not engage in any controversy that might react upon the work to which I am now lending my efforts. I think I can be of more service to the race by giving my time and strength in helping to lay the foundation for an education which will be the permanent cure for such outrages."

"Booker T. Washington Talks." The Daily New Era (Lancaster, Pennsylvania). April 25, 1899. Page 5.

After its initial publication, "The Haunted Oak" was widely reprinted and generated an unusual amount of commentary in the press.

Paul Dunbar has written for the December Century a ballad called "The Haunted Oak." Indirectly it is said to be an arraignment of the civilization that permits the lynching, on suspicion, of members of the poet's race; for the oak is haunted by the spirit of an innocent negro who has been hanged from one of its branches, since which the limb has never put forth leaf.

"Daily Book Chat." The Buffalo Commercial (Buffalo, New York). December 6, 1900. Page 5.

"I oppose the unlawful killing of Indians, Italians, Chinamen, and white men as much as I do that of negroes. It is not a question of nationality or race. I am unwilling to acquiesce to the driveling nonsense of this prejudiced exponent of the gospel, who would ride by night with bands of lynchers to beat down prison doors and lynch a man black or white accused of a crime, while such scenes as Dunbar portrays in his 'Haunted Oak' are enacted."

"Scores Dr. Talmage. Pastor Ransom, Colored, Criticizes His Sermon." The Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois). December 24, 1900. Page 12.